Artwork Details

Among the many fields of Leonardo’s studies there was also engineering.

In fact, in addition to being a painter and sculptor, Leonardo also worked as an architect and engineer especially during his first and longest stay in Milan, which started in 1482 and finished in the end of the century at duke Ludovico il Moro’s court. There he worked as a painter, sculptor, set designer, poet, but also as an engineer and architect, who was mostly designing devices to defend the territory and finding hydraulic solutions for ship logistics.

After Ludovico il Moro was overthrown in Milan (1499) and after a short period of continuous travel in search of a patron who could welcome Leonardo to his court, in 1502 he worked in at the service of Cesare Borgia, duke Valentino, as an architect and engineer, especially for military devices.

Borgia, son of Pope Alexander VI, was the duke of various cities in Romagna, including Cesena and given his warlike nature and reputation as a conqueror, he employed Leonardo to design military and defense machinery for him. Leonardo’s task was to “see, measure and estimate” and to follow Borgia in his military missions.

In 1503 Leonardo was already working in Florence and painting the lost work Battle of Anghiari in Palazzo Vecchio. Some drawings of the work have remained representing studies with modern scientific and mechanical reflections.

Throughout his whole life Leonardo studied, analyzed, engineered and translated his thoughts into drawings and projects. The drawings have been preserved to our days and collected within codes. Some are kept in Milan, at Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana and among them there is the Codex Atlanticus which represents the largest collection of Leonardo’s writings and drawings.

The Codex contains 1119 sheets in twelve volumes which were made between 1478 and 1519 and they were donated to Milan by marquis Galeazzo Arconati, who had them from the previous owner, sculptor Pompeo Leoni.

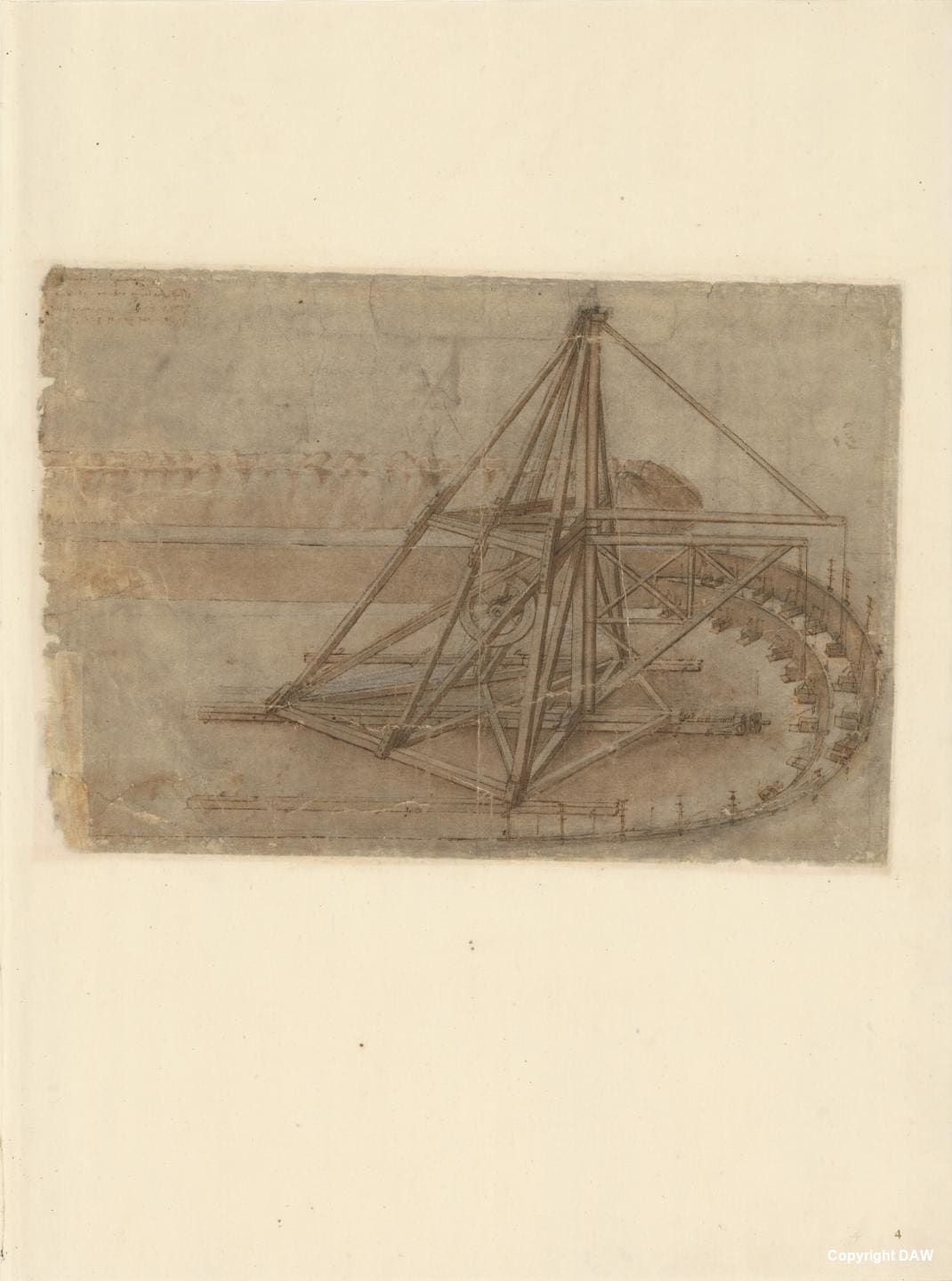

Among Ambrosiana’s drawings here is also this one representing a study of an excavating machine which could be defined as the real ancestor of the cranes which are nowadays used in construction sites. According to Carlo Pedretti, Biblioteca Ambrosiana’s drawing dates back to the early years of the 16th century when Leonardo was once again in Tuscany and studying a project to channel the Arno river.

Often his brilliant intuitions have advanced by centuries the most modern inventions and scientific discoveries, like this drawing that refers to De Architectura (ca. 15 B.C.), the architectural treatise by Vitruvius, and treadmill-powered crane, a machine for lifting heavy elements.

The machine that is described in the drawing consists of a drum with arms operated by a person. Once the arms are put on their place they could unearth clods of soil and dig the ground. The excavation could proceed in sectors and from time to time the machine would have been moved on the excavation area.

Artist Details

View All From Artist

Leonardo was born in Anchiano in 1452. He was an illegitimate son of notary Ser Piero di Vinci who brought him to Florence in 1469 to give him artistic education.

In 1472 he enrolled to the Compagnia dei Pittori and attended Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop, participating also in the anatomical research with Antonio and Piero Pollaiolo.

In 1482 Leonardo moved to Milan to serve Ludovico il Moro. He introduced himself as a musician, painter, sculptor, engineer and architect. He painted several works in the court of Moro, among them the Lady with an Ermine and worked on the equestrian monument for Francesco Sforza.

He was a set designer for various court celebrations and studied hydraulic and military engineering. He also devoted himself to physical and natural sciences, as shown in many of his drawings. His most famous work of this period was the Last Supper in Santa Maria delle Grazie (1495 – 1498) where he experimented with tempera on plaster technique instead of the traditional fresco. This resulted in poor state of conservation, which Vasari already mentions in the mid-16th century.

Ludovico il Moro was defeated by the French in 1500 and Leonardo set off to Venice with his friend, mathematician Luca Pacioli and his student Salai. Then he went to Mantua as a guest of Isabella d’Este and painted her portrait. In the same year he returned to Florence, where he painted Madonna and Child with St. Anne (Louvre, cartoon at the National Gallery of London) and the cartoon for the Battle of Anghiari (1504-1505) for the Salone dei Cinquecento in Palazzo Vecchio.

He was commissioned by the Gonfaloniere of the Florentine Republic, Pier Soderini, who had also commissioned Michelangelo, who was working with the Battle of Cascina. Leonardo experimented with ancient encaustic technique, which turned out to be unsuccessful. Therefore, the project was not completed and today only some drawings have remained of the lost cartoon, such as the Tavola Doria.

Leonardo traveled to Urbino, Pesaro, Rimini and Cesenatico where he continued to study hydraulics, cartography and fortifications, but in 1505 he returned to Milan. He made several trips between Lombardy, Florence and Rome and continued his science research, but he was never commissioned by the Vatican, which favored the works of Raphael and Michelangelo.

Disappointed Leonardo left Italy in 1517 to take refuge in the castle of Cloux, near Ambroise in France, under the protection of Francis I, who gave him an annual pension. He brought numerous paintings with him, like Mona Lisa, which he painted in Florence in 1503. In France he continued his anatomical and scientific studies of which he left many drawings.

Leonardo died in 1519.

Collection Details

View all from collection

Pinacoteca Ambrosiana was established in 1618 by cardinal Federico Borromeo, when he donated his art collection to the Ambrosiana library, which was founded by him as well in 1607. The building was named after the patron saint of Milan, St. Ambrose.

It was the first museum in the world to be open to the public. The history of the Pinacoteca and the library goes hand in hand, as this was also the first library to be open to the public. The book collection includes prestigious volumes, among them Petrarch’s Virgil with illuminated manuscript by Simone Martini and Da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus, donated in 1637 by Galeazzo Arconati.

In fact, cardinal’s plan was to display art with its symbology and evocative power to serve Christian values reaffirmed by the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which were threatened by the diffusion of the Protestant reformation.

The academy was added in 1637 and transferred to Brera in 1776. It was supposed to be an artistic school of painting, sculpture and architecture which would allow the students to learn from the great models of the history.

The building was designed by architect Fabio Mangone (1587-1629) and it is located in the city center. The space is expanded over 1500 square meters and divided into twenty-two rooms. The cardinal illustrated the works and the objects himself in his book in Latin, Museum (1625), which still today represents the main nucleus of the Pinacoteca.

Through commissions and purchases Federico Borromeo’s collection grew with the paintings of Lombard and Tuscan schools, among them works by Raphael, Correggio and Bernardino Luini and casts from Leone Leoni’s workshop, arriving to a total of 3000 artworks of which 300 are exhibited.

There are great masterpieces such as the Portrait of a Musician by Leonardo Da Vinci (1480), Madonna del Padiglione by Botticelli (1495), the cartoon for the School of Athens by Raphael (before 1510), the Holy Family with St. Anne and Young St. John by Bernardino Luini (1530) and the Rest on the Flight into Egypt by Jacopo Bassano (1547).

A great part of the collection is dedicated to landscape and to still life, because the Cardinal saw the nature as an important tool raising the human mind into the Divine. For this reason, Federico collected Caravaggio’s Basket of Fruit and the miniature paintings by Jan Brueghel and Paul Brill.

After the cardinal’s death the collection was enriched with the donations of the artworks from 15th and 16th centuries, such as the frescoes by Bramantino and Antonio Canova and Bertel Thorvaldsen’s marble self-portraits. Museo Settala, one of the first museums in Italy, founded by canonical Manfredo Settala (1600-1680), was joined to Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in 1751. The museum is a sort of science history museum with a variety of curiosities of all time.

During the period of growth, the museum required some structural and architectural changes as well, including the expansion of the exhibition halls between 1928 and 1931, which were decorated with 13th century miniature motifs of Ambrosian codes, and between 1932 and 1938 a new series of restorations was implemented under the guidance of Ambrogio Annoni. The renowned readjustment in 1963 was curated by architect Luigi Caccia Dominioni and the museum excursus was concluded with the current reorganization between 1990 and 1997.